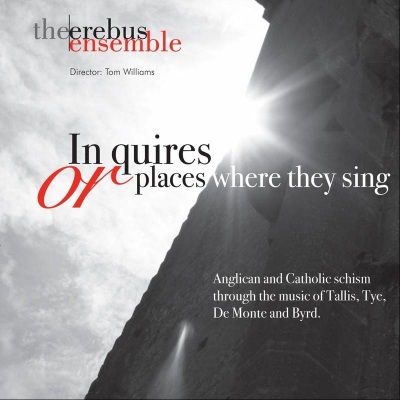

In Quires Or Places Where They Sing

In order to appreciate the wonderful works of the Catholic tradition composed by the likes of William Byrd, an understanding of the established Anglican school must be achieved. That school is wonderfully represented by some sublime anthems by Christopher Tye and Thomas Tallis. Tye’s setting of O come ye servants of the Lord displays all the hallmarks of the conditions imposed on composers writing for the Anglican services following the Reformation. It is set almost completely homophonically, departing from that texture on only two occasions. The two musical sections are each repeated, a technique that became widespread during and following the reign of Edward VI; this was undoubtedly due, in part, to the reformers’ desire for complete intelligibility of sacred texts in the liturgy – a reinforced message in the vernacular. This was of paramount importance in a movement that sought to restore the centrality of God by dispensing with the rich adornments of Catholic music with its Latin texts and complex counterpoint. Thomas Tallis’s anthem Verily, verily I say unto thee is another fine example of this style, but written, of course, by a Catholic composer. The message of the work is clearly conveyed as Tallis sets important phrases of text between periods of pondering silence – ‘for my flesh is meat indeed’ allowed to echo around the cathedral’s vaults, implanting the message into the consciousness of the faithful. The Anglican music of Tallis and Tye was sanctioned, encouraged even, and represented a reformed and repentant church; it was presented with confidence and vigour in a very public way. The Anglican faith was born, and those adhering to the old religion were pushed underground. The centre-piece of this recording, William Byrd’s Mass for Four Voices, was written around 1592 and is reputed to be the earliest of his three mass settings. It is a deeply personal work that gives poignant insight into Byrd’s faith. The consistent polyphonic texture is almost flippant in its defiance of the reforms instituted by the Anglican Church and, indeed, the Catholic Church following the rulings of the Council of Trent. It shows none of the stylistic traits of the Italian settings of the High Renaissance for example, with little use of homophony or antiphony, instead displaying a dense contrapuntal texture throughout. The Mass for Four Voices is intimate and austere, and serves as a prime example of Byrd’s recusant music – an offering of prayer, not art. The Gloria provides perhaps the only exception to an overall mood of subdued resignation, the lower voices piercing the texture with fanfares of praise at the words ‘Laudamus te’, representative perhaps, of Byrd’s personal resilience in the face of adversity. The remainder of the setting is extremely dark and conjures vivid imagery of the damp underground chambers in which this music was secretly performed. The Agnus Dei is the most desolate movement of all, opening with an isolated conversation between soprano and alto before a repetition of the material in the restored four voice texture. This acts as an introduction to the ‘dona nobis pacem’ set to a series of agonising suspensions that are matched in their sadness only by their inherent beauty. Byrd was arrested on the charge of recusancy several times after his refusal to sign the oath that recognised Elizabeth I as the Head of the Church, and paid heavy fines throughout his life. The fact that he avoided incarceration (or worse) is attributable to his personal relationship with Elizabeth, the monarch with a great love of music and an even greater need to maintain a strong public image. The skill of composers such as Tallis and Byrd did much to enhance what Roy Strong coined as the ‘cult’ of Elizabeth, and, to this end, it was prudent for the Queen to keep them close. Furtherance of Elizabeth’s persona came in many forms but perhaps none more glorious than Byrd’s adaption of Psalm 21 for the prayerful anthem, O Lord, make thy servant Elizabeth our Queen. Stylistically, the work could not be further from the austerity of the contemporaneous Mass for Four Voices, with its juxtaposition of homophony and counterpoint, bold false relations and joyous melodies. Byrd paints the text beautifully here, illustrated particularly at the words ‘And give her a long life’, with ‘long’ being set to the largest time duration in a stunning echo motif that is heard across the six-part texture. Byrd’s relationship with the Franco-Flemish composer Philippe de Monte has long been considered by scholars of this period, but the existence of a personal friendship remains unlikely; there is no firm evidence to suggest that the two men ever actually met. It is clear, however, that Philippe was acutely aware of the politico-religious situation in England. He had served under Philip II of Spain and thus spent time in England’s Catholic court under Philip’s wife, Mary Tudor. His coded setting of the opening words of Psalm 137, Super flumina Babylonis, was sent to Byrd amid the height of recusant hardship, and the work’s stark intent is clearly that of a sympathetic gift which acknowledges the English composer’s isolation. The lines ‘How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?’ holds particular resonance, as is clear from Byrd’s response, Quomodo Cantabimus, which opens with the same text. De Monte’s setting has a pervading air of dejection and his use of antiphony between the two four-voiced choirs creates the feeling of unending questioning, with one choir stating the musical theme only for the other to repeat it. If this technique suggested in any way that Byrd was wavering in his quest for the answer to the question posed, then his setting of Quomodo dispels all fears. His motet triumphs from the opening bar with a bold descending triad which is developed into a complex three-voice canon, creating a firm and dense texture that looks strong on the page and sounds resolute in performance. If this musical charge is not enough to convince Philippe de Monte of Byrd’s position, the latter’s choice to set verse five of the psalm surely does: ‘If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning.’ from the Director: As a church musician, the Book of Common Prayer rubric, ‘In Quires and places where they sing, here followeth the anthem’ has long been embedded in my consciousness. When the phrase was first published in the 1662 prayer book its meaning was obvious but it was during my personal exploration of the music of an earlier age that the words began to take on an added resonance. Choir trainers across the world inspire their groups with such phrases as ‘performing the music in the place for which it was written’ and ‘hearing the music in its natural acoustic.’ All this is very exciting for a performer – a connection with history, for, after all, music is living history. A brief study of the Tudor period quickly establishes the fact that a great deal of this music was not heard in our ancient cathedrals, however, but performed in very different places. The Tudor world in which Catholic composers such as Tallis and Byrd lived was a place fraught with danger; religious persecution was rife and the battle to survive whilst staying true to their faith became the treacherous way of life. One thing that is clear is that out of these hellish circumstances rose some of the most divine music of all time. Whether it was written for the Anglican Church and performed in the quires of cathedrals and parishes for all to hear, or for the Catholic rite and banished to cellars, priest holes and secret chapels, this music was representative of humanity – fear, faith, love and joy encapsulated in high art that has stood the test of time and continues to be relevant five hundred years on. Tom Williams, Founder and Director, The Erebus Ensemble